Copyediting, line editing, development editing, oh my!

Maybe you know you need an editor, but you may, like many other authors, be a little vague on the different kinds of editing that go into making a commercial-quality book.

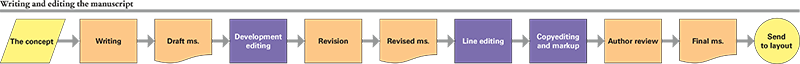

Editors and editors’ professional organizations vary in the exact terminology they use for the different stages of book editing, but conceptually, they all align pretty well. Here’s my version:

- Manuscript assessment. This is a quick look to determine what kinds of editing will be needed for this book. I do this as part of the engagement process and do not charge for it.

- Manuscript evaluation. This is a partial or complete read-through that results in a professional editor’s written opinion regarding additional work the author needs to put into writing and self-editing before the book is ready for line editing. This is less extensive (and less expensive) than full-on development editing, and it may be a good choice for less-experienced authors before they invest a lot more into the project.

- Development editing. The development process varies depending on the nature of the book. For a novel, a memoir, a biography, or a history, for example, the editor will focus on storytelling, including plot structure, character development, scene setting, timeline, verisimilitude, and other big-picture aspects. For a business management book, a how-to book, or a self-help book, the editor is looking at logical organization, how different types of information are segregated and labeled, whether the author is staying on topic or wandering off, whether the content is timely, relevant, and useful, and so on. In all categories, development editing is looking at the broad outline, not the low-level details like spelling and punctuation. Are the ideas there, and are they clear enough for a line editor to make sense of them? The editor’s thoughts are communicated in an editorial letter or in comments written directly in the manuscript or in a combination of those. Sometimes a development editor will rearrange large blocks or even whole chapters directly rather than asking the author to do so.

- Line editing. Line editing looks at your text at the paragraph, sentence, and word level, with the goal of having the text read well. The line editor is working for the reader as much as, perhaps more than, for the author, to ensure that the text is clear in meaning, uses appropriate vocabulary, and still sounds like the author. A good line editor is a reader-whisperer.

- Copyediting. By the time a manuscript is ready for copyediting, the words should all be correct and in the right order, and none of them should be spelled wrong. But are they spelled consistently? (Many words have more than one correct spelling.) Is the capitalization and punctuation consistent? Are the reference citations formatted consistently? Are numbers rendered according to some consistent set of style guidelines? Is that historic figure’s name the one the author meant, or did the author pick the wrong person with a similar name? And what year were they really born? Does Main Street actually intersect 1st Street in that city, or should that be 1st Avenue? Was there scheduled air service between those two cities in that year or not? The copyeditor checks all of those details, makes sure the URLs resolve correctly, and tries to verify anything that looks even a little bit suspect. The short version: copyeditors look stuff up. All the time.

One editor may do more than one kind of editing and may combine two or more types of editing in a single round of edits. That’s okay. The above definitions should help you sort out the kinds of editing you need. The other thing to notice is that I did not mention proofreading. That’s because proofreading comes later. It’s not part of the manuscript editing process at all.

Working with an editor

Once you have completed your draft manuscript and are ready for an editor to look for it, you have to take off your author’s hat and put on your publisher’s hat. Publishing is a product development business, and product development is a team sport. You want to pick the best team you can find, but then you have to trust your teammates to work on your behalf.

Every editor has their own working style, and you may find you click with some better than with others. That’s okay. I’m a good editor, respected by my colleagues and my clients, but I may or may not be the best editor for you. One way to decide what editor or editors you want to work with is to request sample edits. The best way to request them is to send the entire draft manuscript to a few editors and allow the editors to select a brief passage (typically no more than about a thousand words) and show you how they would edit that. Some editors may ask you to pay for the sample edit, with the amount credited against your eventual bill if you decide to work with them. Other editors don’t charge for the sample. (I don’t.) One thing all editors agree with, though, is that the author shouldn’t be the one selecting the pages to edit. After you receive the samples, review them to see if the editor is someone you want to work with. You’ll probably find a wide range of quoted prices, too. But you should not make the decision solely on price. Once you’ve selected the editor, that person will probably have some procedures they want you to follow in the course of the edit. You will have the best experience and get the best results if you carefully follow instructions. Failing to do so can result in delays, higher bills, and a lower quality in the finished book.

When you’re ready

When you’ve gotten your manuscript as good as you can on your own, I’d be glad to do a quick assessment and, if I think it’s ready for one, a brief sample edit for you to review. Complete the project questionnaire and follow the instructions there for uploading your manuscript.