You want your own artwork featured in your book. Maybe you’ve illustrated a children’s book. Maybe you’re a painter and you want to have a coffee table book. Maybe you’ve done just one fabulous painting for the cover. Whatever the case, this post is about getting your work in traditional media onto the printed page. If you have created your work in a digital medium to begin with, none of this applies to you.

Following these instructions will result in the best possible reproduction of your work at the least cost.*

- Mount the unframed artwork on a vertical surface.

- The room should be uniformly and brightly lit with “daylight” white (5000K) lights.

- The camera should be mounted on an adjustable tripod.

- The lens of the camera (look at the back of your phone and note that the lens is not geometrically centered on the phone body, so always measure from the actual lens) should be at the same height from the floor as the center of the artwork. Use a tape measure. Don’t guess.

- The lens of the camera should be aligned left-to-right with the center of the artwork, on a line perpendicular to the wall. Use a carpenter’s square or the equivalent to establish the perpendicular line. Don’t guess.

- The camera should be moved forward on that perpendicular line until the artwork almost (but not quite) fills the frame.

- The photo should be taken at the camera’s highest resolution.

The camera will save the image in JPEG format. Once you have all the images in a folder, you can change their names from the simple sequence number the camera provides. You can change the name to a short title of the work, but you should also include a sequence number for where the work appears in the book: 001apple.jpg, 002bumblebeeEatingApple.jpg, 003catPlayingWithBumblebee.jpg. Note that there are no spaces in the example filenames. That’s a good practice to follow.

Do not, for the love of all that is holy, open the image in Photoshop or any other image editing program. Doing so, even for something as simple as cropping it to size, degrades the image when you resave it. JPEG is a “lossy” file format. Please just send the images, with their new names, to the designer (preferably me, of course). The designer will handle the image in a way that circumvents loss and will make any needed adjustments to the image.

* I did a coffee table book some years ago for an artist who promised me that she would provide digital photos of all her paintings taken by a famous photographer whose work hung in museums. Well, the famous photographer whose work hung in museums placed each painting in turn on a tilted easel twenty or so feet from the camera in a dark room and snapped a single photo with a handheld camera from some random angle. Boy, that was a fun job. Not. I should have charged more.

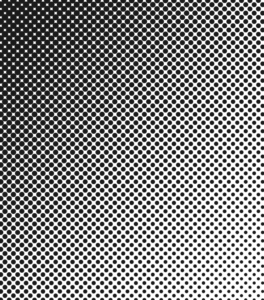

So how does a black-and-white image (a picture, as opposed to type or a vector diagram) get printed? It begins with a halftone screen. This is an old analog technology that is modeled in modern image-processing software. In the analog world, a photo was placed on a copy board, and a photograph was taken of that photo with a piece of ruled film in front of the new film that was to be exposed. The rulings on the face of the film (the halftone screen) caused the light reflected from the image being photographed to diffract on the way through the thickness of the screen, producing halftone dots on the new film. Those dots were proportionate in area to the amount of light coming through that particular rectangle on the screen. So the dots varied in size. If you stood far enough away from the photo, it did not look like a rectangular array of oval dots; it looked like a continuous tone image, like the original. The spacing of the rulings on the screen determined the quality of the printed image. A newspaper might have used an 85-line screen, that is, a screen with 85 lines per inch. A weekly magazine or a history book might have used a 110- or 133-line screen (133 being considered good quality). A monthly might have used a 150-line screen. I think National Geographic used 175, and some art book printers used 200 lines per inch. At 150 lines per inch, a halftone dot occupies an area 16 printer dots square, any fraction of which can carry ink. But if you look at any halftone image, either black-and-white or color, under a magnifying glass, you can clearly see the halftone dots, in all their various combinations of sizes and grid orientations, that make up the image. (If you don’t want to squint through a magnifying glass, you can just look at paintings by Chuck Close, who exploited the halftone illusion in his wall-size portraits.)

So how does a black-and-white image (a picture, as opposed to type or a vector diagram) get printed? It begins with a halftone screen. This is an old analog technology that is modeled in modern image-processing software. In the analog world, a photo was placed on a copy board, and a photograph was taken of that photo with a piece of ruled film in front of the new film that was to be exposed. The rulings on the face of the film (the halftone screen) caused the light reflected from the image being photographed to diffract on the way through the thickness of the screen, producing halftone dots on the new film. Those dots were proportionate in area to the amount of light coming through that particular rectangle on the screen. So the dots varied in size. If you stood far enough away from the photo, it did not look like a rectangular array of oval dots; it looked like a continuous tone image, like the original. The spacing of the rulings on the screen determined the quality of the printed image. A newspaper might have used an 85-line screen, that is, a screen with 85 lines per inch. A weekly magazine or a history book might have used a 110- or 133-line screen (133 being considered good quality). A monthly might have used a 150-line screen. I think National Geographic used 175, and some art book printers used 200 lines per inch. At 150 lines per inch, a halftone dot occupies an area 16 printer dots square, any fraction of which can carry ink. But if you look at any halftone image, either black-and-white or color, under a magnifying glass, you can clearly see the halftone dots, in all their various combinations of sizes and grid orientations, that make up the image. (If you don’t want to squint through a magnifying glass, you can just look at paintings by Chuck Close, who exploited the halftone illusion in his wall-size portraits.)